Literacies in Action

by Staff | May 18, 2020

This morning in our team huddle, Ms. Danielle, our STEAM Coordinator, shared a story with us. It included chat messages between two students. She wanted us to see how one of our newest and youngest students, an 11-year old girl who arrived in the US in January 2019, had been exchanging chat messages with another newcomer student in order to help her join Friday’s Last Day of School Zoom Party. These two particular students are both in our Level 1-Newcomer Class and had been working on Google Classroom and using Google Hangouts over the last months, but were not familiar with Zoom yet. Ms. Danielle shared information with them earlier in the week in technology class about Zoom. She had given them passwords and pictures to show clearly where to look on the iPad screen and assist them in logging on later. Ms. Danielle saw these two newcomer students messaging and chatting during the Zoom event and recognized how they had powerfully taken up newly learned literacy practices to support each other.

The 11-year old student who could not read or write in English before coming to our school in August 2019 was writing clear, concise, and coherent chat messages to her friend in order to help her get into the Zoom meeting. She encouraged her not to give up and gave her the password and instructions. Meanwhile, the student desperately trying to join the Zoom, took screenshots of her iPad to show what she was seeing and doing, as she struggled to get on. These two young women engaged in a full back and forth conversation using multiple types of literacy practices in order to take part in something that they were invested in doing. They wanted to be on the Zoom with their friends and teachers. They didn’t want to miss the last day of school celebration. Eventually, they both succeeded.

These two young women used English print literacy practices, writing messages and texts to each other. They took up digital literacy practices, using the iPad and online applications to communicate, and they took up other multimodal literacies as they took screen shots and used software tools to draw circles and point out what they saw. Once on the Zoom, these two chatted in the side chat section, typing words and using emojis to communicate their joy in joining the party. Then, they cheered and sang songs with the rest of our school.

In one hour, these students engaged in multiple literacy practices using multiple modes for communication. They showed clearly how literacy is tied to empowerment, investment, agency, and action. They also showed how, given the opportunities, students can become teachers. Ms. Danielle modeled for them how to use screenshots and other tools for support in technology classes. Then, when the opportunity arose, they were ready to use the same tools to teach and support each other. As a literacy and language educator, I can’t think of anything more powerful than stories like these. Ultimately, this is what all educators want for students—enough understanding and social support to take up and use the knowledge, skills, and tools they have been taught to reach their goals and teach others.

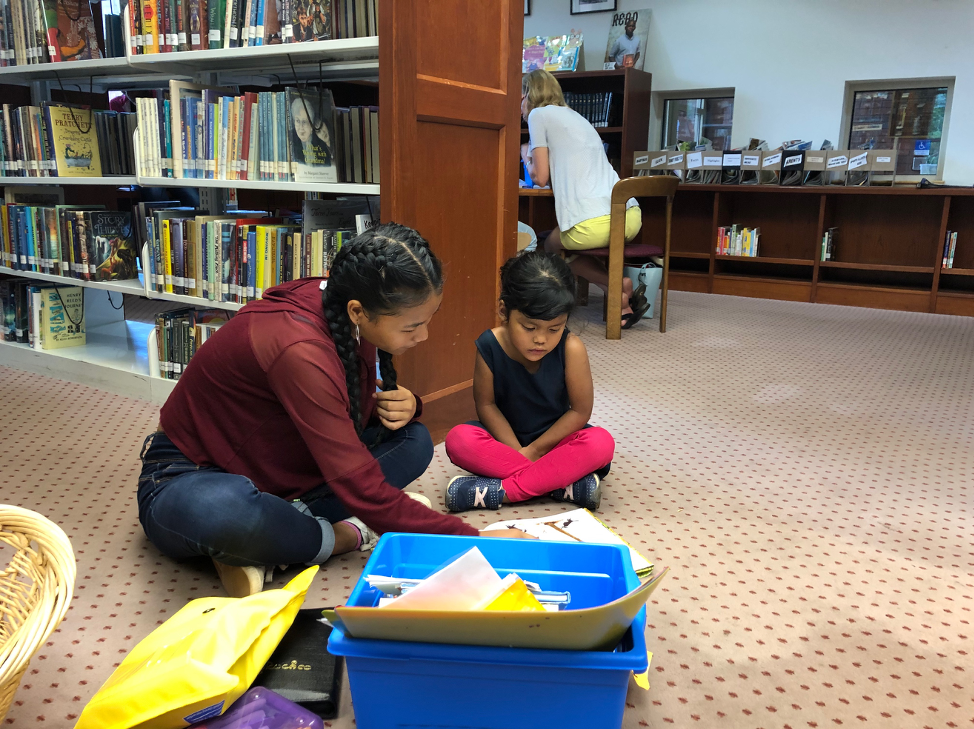

There have been times at GVP when we have accepted students into our school who are already 18 years old. Typically, the students we meet at this age have been resettled into the US with limited English and print literacy proficiency, and the risk of them dropping out of a traditional high school is high. We have seen several students at GVP who came to the US believing that they would have a chance at the education they never had and then quickly realizing how challenging that was going to be. When these young women come to our school, they are often insecure and unsure. They realize how far they have to go. We recognize that, too, and try to explain that the journeys and destinations may be different for them. Research shows that older newcomers who do not have literacy in their first language often face real challenges in learning literacy for the first time in a foreign language. It often takes longer and requires years of practice that are not always available as they reach the cut-off ages for high school registration. It is a kind of race against time for these older newcomers.

At GVP, these students are committed to learning and often see several grade levels of literacy growth in their first year. Their hard work during their time at GVP makes it possible for us to quickly move them on into high school, where we know that the challenges will remain, but hope that they will accomplish what they desire by moving on. Some of these students have remained in high school, some have graduated from our local alternative school, and some never graduated and went on to work to support themselves and their families. Whatever the outcome, I am deeply grateful that they were able to gather the literacy, support, and confidence in their time at GVP that they needed. I know that when these students leave GVP, they can navigate everyday lives with the literacies they have learned. They no longer have to be afraid of riding on the bus or train for fear of not knowing the directions or stops; they no longer have to fear filling out an application online; and they have met other teachers and school sisters who can help support them with things that are too difficult to manage alone. They have learned how to use literacy brokers as resources and also become literacy brokers for others.

Literacy brokering, while defined in diverse ways, is generally understood as social practices in which one person facilitates meaning making (usually involving printed texts) for or with another party (such as a parent or neighbor), who has different linguistic and/or cultural backgrounds and needs assistance. Unlike formal interpreters and translators, brokers mediate, rather than merely transmit, information. They help negotiate meaning in a given social or cultural context. The students at GVP typically take up roles as literacy brokers very early on in their educational process. They help their parents with newsletters, permission forms, flyers, health forms, bill paying, applications, and so much more. While they are still emerging as English readers and writers, they are already practicing sophisticated mediation and negotiation to make sense of text and act on their worlds. This is why real-world authentic literacy tasks that are related to students’ lived experiences are so important to learning.

Bonnie Norton, a Canadian educator, researcher, and scholar, has highly influenced my own perspectives into learning. She argues that motivation is a concept often understood as intrinsic and unchanging; something a student either has or doesn’t. Motivation is typically removed from the social context and often doesn’t work as a concept when trying to make sense of students’ learning. Instead, Norton urges educators to think about the concept of investment–a a student’s investment in learning a language. Learners will be invested if they can see and understand the value and usefulness of the learning or practice in their everyday lives and futures.

Learning should be related to students’ identities, desires, and hopes for the future. It is more likely that students will invest in learning when they see the material, cultural, and social value of it. It is critical that schools and teachers put students at the center of our work and seek to engage them fully as humans in learning, especially during this unprecedented pandemic. We must remember that our students are living and changing social beings with real needs and desires, and that those things influence and make a difference in their learning. For the two newcomer students in Ms. Danielle’s story, their desires to be part of the community and to support their friends made taking up and practicing new literacies valuable and useful. At GVP, we are focused on keeping our students at the center of our work and providing access to learning that is worth investing in. Our goal is to provide an education that matters and makes a difference in students’ everyday lives and futures.

“Though we loved school, we hadn’t realized how important education was until the Taliban tried to stop us. Going to school, reading and doing our homework wasn’t just a way of passing time, it was our future.” – Malala Yousafzai

“Acquiring literacy is an empowering process, enabling millions to enjoy access to knowledge and information which broadens horizons, increases opportunities and creates alternatives for building a better life.” – Kofi Annan

“Literacy is not a luxury, it is a right and a responsibility. If our world is to meet the challenges of the twenty-first century we must harness the energy and creativity of all our citizens.” – President Bill Clinton