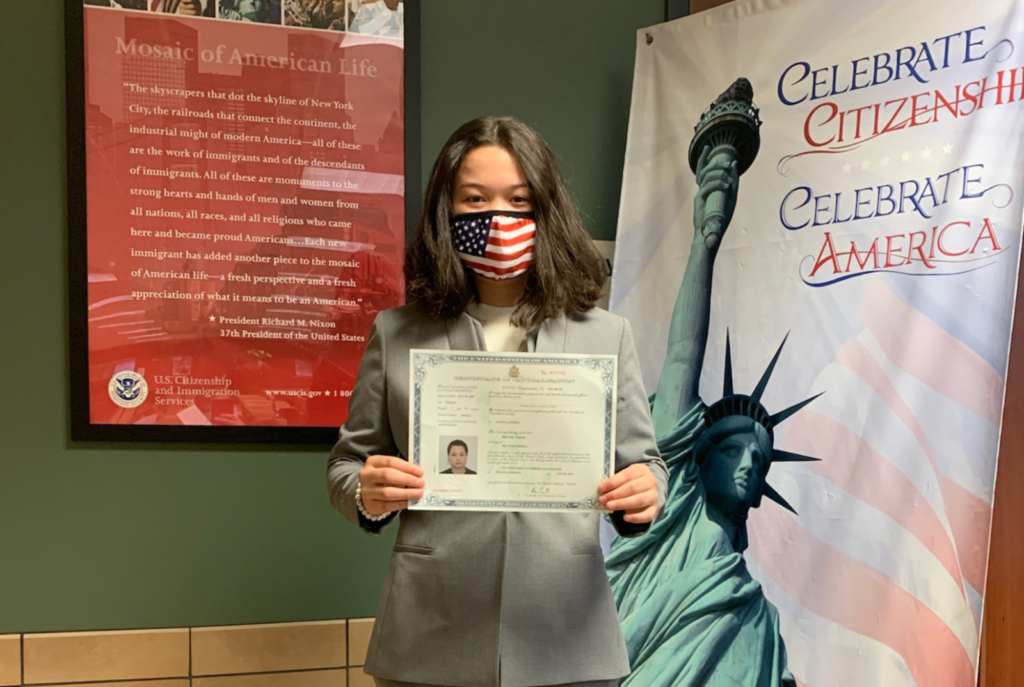

GVP Alumna Becomes a U.S. Citizen, Votes for the First Time

by Jennie Jiang | October 27, 2020

Voting this election cycle has taken on added importance and urgency for most of us – but even more so for 20-year-old GVP Alumna Khaty Barati, who recently cast her first ballot in a U.S. election after being granted U.S. citizenship just months earlier.

“I felt so good and proud,” Khaty says. “I want my voice to be heard. I had to give up my right – not my right, but my privilege – in my old country to be able to be counted as an American.”

For Khaty and her mother Khadija, the road to U.S. citizenship – and their right to vote in this election – has taken no less than five years and nine months. Along with Khaty’s younger sister Farzana, the two have been living in the U.S. since 2014, when they first arrived as refugees from Afghanistan. As green card holders, Khaty and her mother haven’t been able to vote in any U.S. election despite having lived and, for Khadija, worked here for years. They also couldn’t travel outside the country, though it was technically legal for them to do so. They were too afraid of potentially being denied entry back into the U.S. to even go visit their family members, all of whom remain in Afghanistan.

For Khaty and her mother Khadija, the road to U.S. citizenship – and their right to vote in this election – has taken no less than five years and nine months. Along with Khaty’s younger sister Farzana, the two have been living in the U.S. since 2014, when they first arrived as refugees from Afghanistan. As green card holders, Khaty and her mother haven’t been able to vote in any U.S. election despite having lived and, for Khadija, worked here for years. They also couldn’t travel outside the country, though it was technically legal for them to do so. They were too afraid of potentially being denied entry back into the U.S. to even go visit their family members, all of whom remain in Afghanistan.

To apply for U.S. citizenship, Khaty and her mother first had to wait the mandatory five-year period as lawful permanent residents. During this time, Khaty navigated the challenges of learning a new language and adjusting to a new cultural and educational environment. Because she was 14 years old when they moved to the U.S., Khaty was placed into ninth grade at Clarkston High School – even though she couldn’t speak English and didn’t have math skills beyond basic addition and subtraction. “I failed all my classes,” Khaty recalls. “I started hating school. I would get lost just getting to my classes. And every time a teacher would talk, I felt like they were rapping.”

Then she heard about Global Village Project through Steve Heckler, a GVP Board member whose church had welcomed Khaty and her family to the U.S. on their very first day. Steve, who would eventually become Khaty’s and Farzana’s GVP mentor, told her about a school designed to meet the needs of refugee girls, and she knew she had to go. Even though returning to middle school meant she’d always be in a different grade than others her age, Khaty says, “That was the biggest decision I had to make, for my own good, for my own future. Because if I would have stayed in that high school, I don’t know where I would end up today.”

Though she could talk “all day” about GVP, Khaty says that what she loved most was the teachers: “At GVP, the teachers are like your sister or your second mother… the minute you walk in, you feel, you know, the love… the respect, everything.” Khaty graduated from GVP in 2017 and went on to attend Druid Hills High School. Though she says she struggled to make friends among students two years younger than her, she excelled nonetheless, graduating in just three years.

Though she could talk “all day” about GVP, Khaty says that what she loved most was the teachers: “At GVP, the teachers are like your sister or your second mother… the minute you walk in, you feel, you know, the love… the respect, everything.” Khaty graduated from GVP in 2017 and went on to attend Druid Hills High School. Though she says she struggled to make friends among students two years younger than her, she excelled nonetheless, graduating in just three years.

It was during Khaty’s last year of high school that she and Khadija became eligible to apply for U.S. citizenship, the first step in a process that typically takes several months to complete. After submitting their applications, Khaty and Khadija spent the next few months studying together for the citizenship exam, which requires applicants to know the answers to one hundred questions, out of which ten will be chosen at random. The open-ended questions span everything from citizens’ rights and responsibilities, to the U.S. government, to American history and geography. That was the “scariest, and most nerve-wracking” part, Khaty says. If an applicant isn’t able to answer six out of ten questions correctly, they have to wait three months before they can try again. Khaty and Khadija also worked with a lawyer to make sure that all their documents were in order, as even the smallest error could cause delays or even denials to their applications.

Khaty and Khadija had their appointments to take the test and complete their interviews – during which English proficiency is also assessed – towards the end of 2019. They felt a huge wave of relief upon getting an email notification that they had passed: the hardest part was over. All that was left to do was to wait to receive a date for their oath ceremony.

This crucial last step took several stressful months – so long that Khadija became concerned their oath ceremonies were being delayed in order to prevent them from voting in the 2020 presidential election. By June, she was forced to consider a lawsuit, but the day she was ready to move forward with it, they received notice that their oath ceremony had been scheduled for the first week of July! Khaty was thrilled when the long journey was finally complete: “I was extremely happy to finally have the certificate that says I am a US citizen, after so long… at that moment, I was like, ‘I really don’t care. It was worth it.’” (Steve Heckler, dressed as Uncle Sam, also joined Khaty and Khadija at their oath ceremony! See below.)

Khaty is now a first-year student at Georgia State University, and she hopes that others will join her in using their voices to advocate for a more inclusive future. “Not a lot of people… really understand what immigrants go through,” she says. “In our histories, we had immigrants coming into the United States… for a safer place, as other countries went through a lot – you know, wars, having other people take over their country…” When asked what she wished others understood about what it’s like to be a refugee, she said, “Those immigrants that have to come to the United States… some of them really don’t have a choice.”

Khaty is now a first-year student at Georgia State University, and she hopes that others will join her in using their voices to advocate for a more inclusive future. “Not a lot of people… really understand what immigrants go through,” she says. “In our histories, we had immigrants coming into the United States… for a safer place, as other countries went through a lot – you know, wars, having other people take over their country…” When asked what she wished others understood about what it’s like to be a refugee, she said, “Those immigrants that have to come to the United States… some of them really don’t have a choice.”

She hopes the message will reach the ears of those in power. It has been a “very long journey,” Khaty says, for her to get to where she is now. Even if they’ve “never been through this stuff… never walked in our shoes,” she says, “I wish, you know, a president can understand what immigrants go through.”